Foreword

New metaphors are capable of creating new understandings and, therefore, new realities. This should be obvious in the case of poetic metaphor, where language is the medium through which new conceptual metaphors are created.

George Lakoff, Metaphors We Live By

My training as a computational linguist has primed me to hunt for metaphor. In semantics class we read classic works of George Lakoff. Over drinks my lab mates and I would wax philosophical about how metaphorical thinking is at the core of human cognition. While metaphor has never played directly into my research, awareness of it has altered how I perceive the world, and it has given me a tool to tie my educational background to my other passion – martial arts.

Over the years many people have shared metaphors that describe facets of pencak silat. Some have featured plants (trees, rice stalks), nature (waves, animals) and even food (ice cream, burgers). I’ve seen silat described as music, cooking and communication. The parallels between these often relate to skills progression, adapting to purpose and adding one’s own flavor. While any of these metaphors can be extended to encompass more, the Inti Ombak Pencak Silat (IOPS)s as a House metaphor is thus far the most complete I’ve encountered. It highlights key themes of Javanese culture and spirituality, it brings together the broad base of IOPS knowledge, and it presents a framework for teaching and learning the art.

This architectural metaphor has been locked inside Guru Daniel’s brain for decades. Over the past month, as I asked questions about the Inti Ombak curriculum, aspects of this metaphor started to leak out. Guru Daniel and I share a background in engineering, and the bits he shared quickly resonated with me. Our conversations inspired me to further research his breadcrumbs and synthesize what I found into this writeup.

Introduction

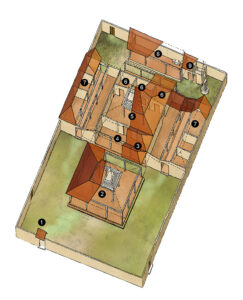

Houses and buildings feature prominently in Javanese philosophy. The Javanese word for a house complex is Omah derived from Oom (Sky) and Mah (Earth) [1]. Taken literally this can be interpreted as roof and floor, but there are multiple layers of meaning and metaphor. For example the front of an ideal omah includes a pendhapa, a semi-public veranda for socializing that juts out from the front of the complex. The chamber where the family resides is referred to as the dalem or omah buri – not without coincidence the Indonesian word for inside is dalam. Pendhapa and dalem represent male and female, just as sky and earth do in many Javanese creation stories.

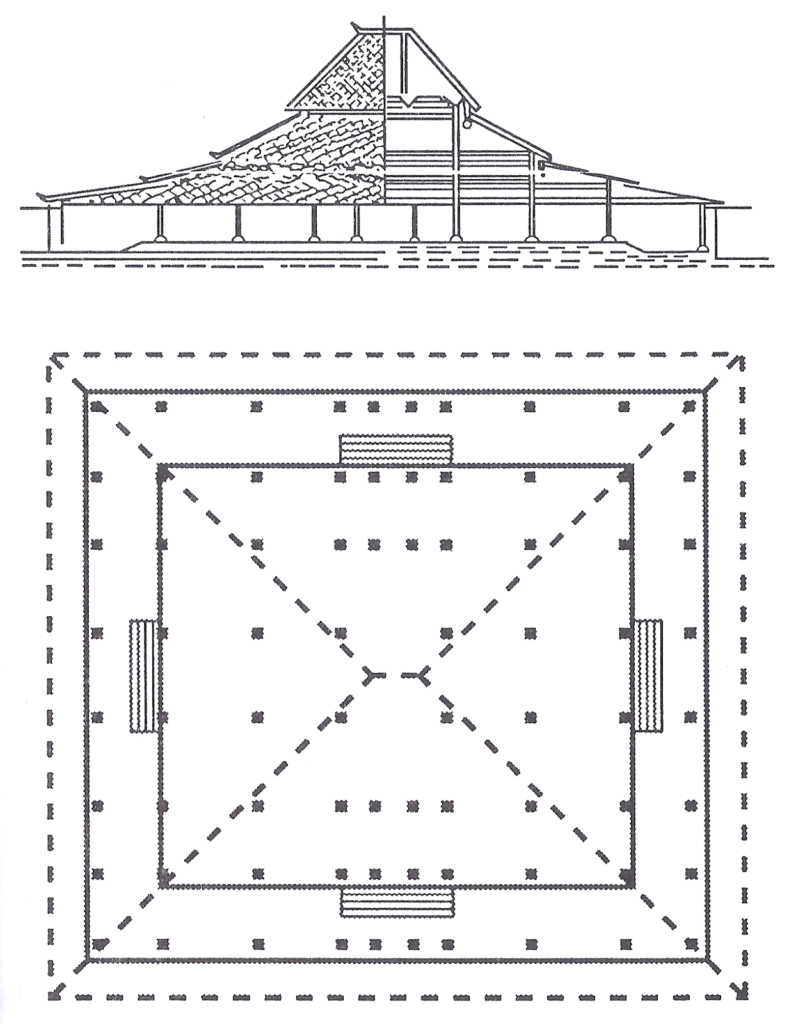

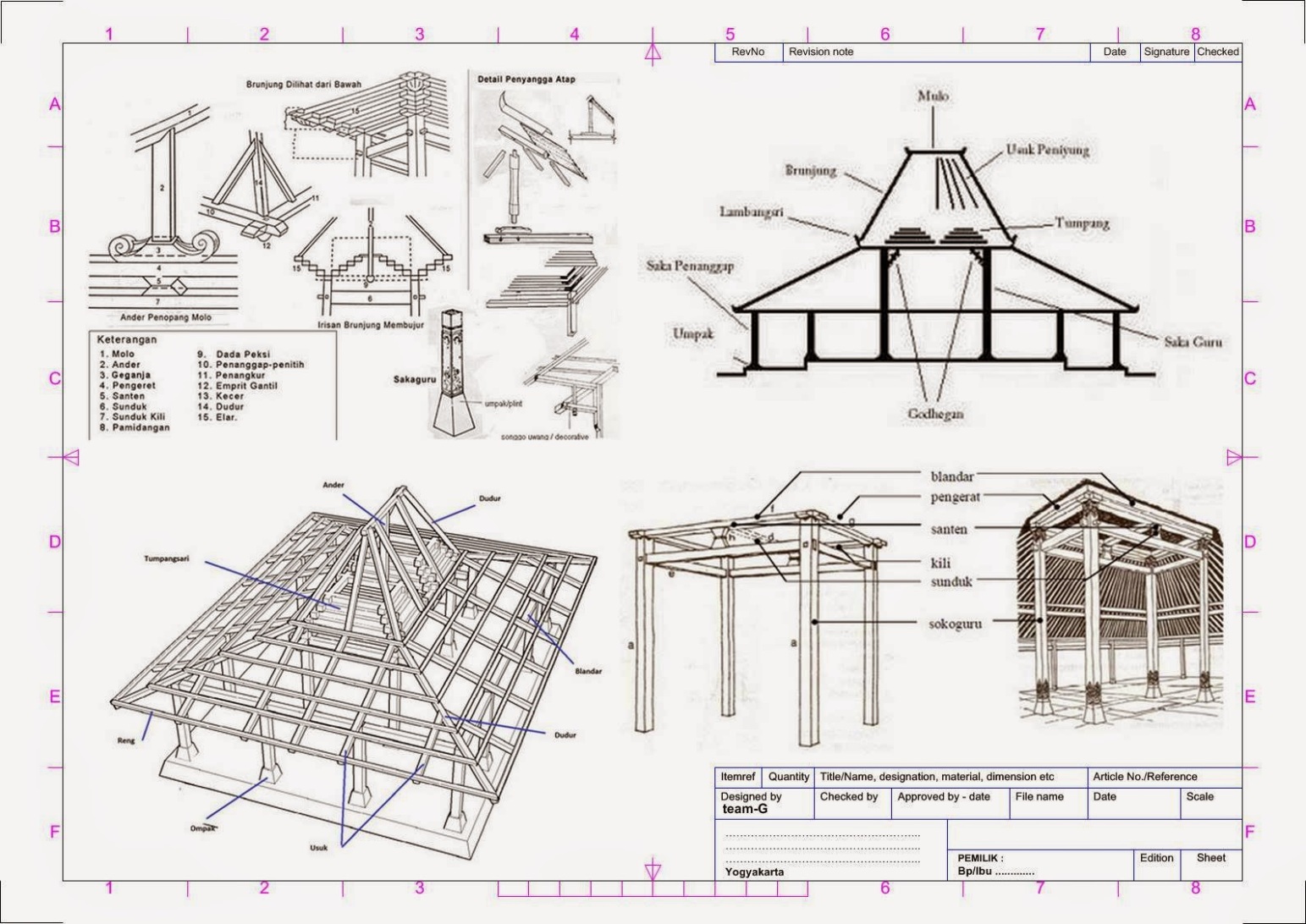

Javanese architecture represents society and functions in tandem with the environment. Nowhere is this more prevalent than in Joglo architecture — the most iconic and complex of Javanese rooftop architectures. Joglo features central pillars that support the highest point while its outermost pillars are much lower. Long before the invention of climate control systems, Joglo have provided a way to manage the sweltering heat of equatorial Indonesia. The elevated central roof draws heat away from the lower areas [2]. The combination of philosophy and practical local wisdom (arifin lokal) weaves its way through all facets of Javanese life, and it is seen in spades in Pencak Silat.

This document aims to build appreciation for the arrangement and organization of the knowledge packed into Inti Ombak Pencak Silat. Drawing parallels between the components and structure of traditional Indonesian architecture and the jurus of Inti Ombak Pencak Silat drafts the blueprint to build the House of IOPS.

A poem

As you walk the spiral of Inti Ombak learning, use this poem to reflect upon where you are and where you are headed in your journey.

Rumah Adat Inti Ombak

Prepare the land

Protect what is essential

Redirect and release what is not

Orient your entryway

Open and close to the south

Accept what is to come

Lay the foundation

Strength is not always visible to the naked eye

Complexity emerges in layers

Raise the pillars

Four posts held together with pins and holes

Their strength and beauty come from each other

Distribute the load

From peak to eave everything connected

A broken link compromises all

Assemble together as one

When a house is complete

It is a microcosm of the universe

Seek shelter not isolation

A feral creature is dangerous

But even the rawest instincts can be trained

Take refuge not retreat

The elements spin a cycle of destruction

But creation arises from impermanence

Venture out to the world beyond

Strong or weak, esteemed or unknown

A whole person is open to new possibilities

– by Lee Becker

The House of IOPS Metaphor

Guru Daniel studied civil engineering in college in part because of his fascination with structure and patterns. This skillset is one he applies to pretty much everything he does. He is also one that likes to tie together many seemingly disparate concepts. If you study silat with him for long enough, you see that the same silat jurus can be used for self-defense, meditation, healing and more. It is no surprise that in organizing his knowledge of Pencak Silat, he drew upon lessons learned from civil and architectural engineering. If you look at IOPS through the lens of structural engineering, the House of IOPS metaphor emerges.

The following section map aspects of traditional Javanese construction to the IOPS jurus. The descriptions below aim to give students of IOPS not yet familiar with Indonesian customs enough cultural context to make the metaphorical link. At the same time, care was taken not to give away every detail to allow learners to explore and draw their own connections.

Jurus Tangguh Geluk

Practitioners of IOPS in the United States often refer to the first jurus they learn as Jurus Satu (1) or simply Satu. This is then followed by jurus dua (2) and tiga (3). Technically these foundational jurus belong to a series known as Jurus Tangguh Geluk.

Tangguh Geluk is Indonesian for spillway. In civil engineering “A spillway is a structure used to provide the controlled release of flows from a dam or levee into a downstream area” [3] In wet, tropical Indonesia, spillways are needed to prevent flooding and destruction of the land. In many cases they are required to make the land usable.

Jurus Gebyok

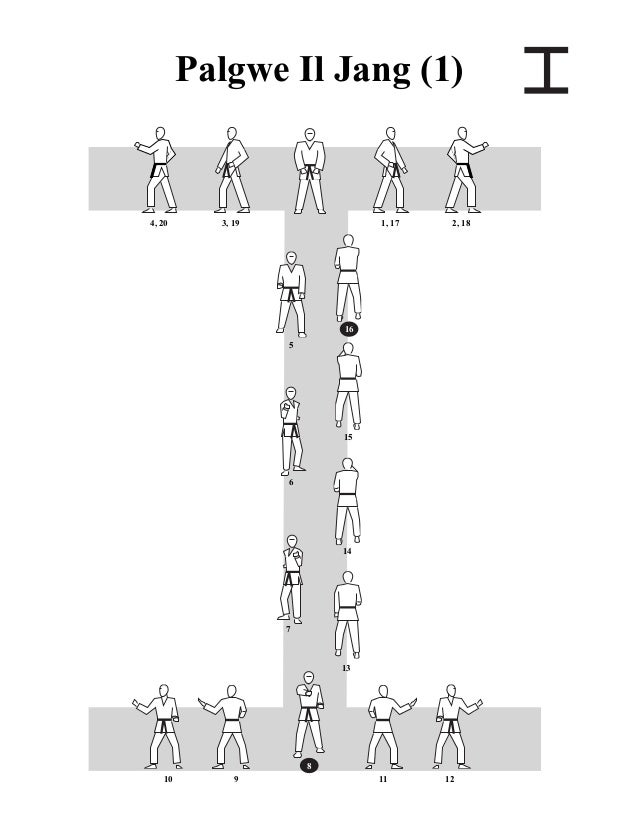

Source: Tae Kwon Do poomse

Jurus Dasar Umum or the Universal Jurus are characterized by their “H” or “I” shape with motion repeated in the four corners and traversal between them. In Indonesian the word umum can mean public, general or universal. All three meanings apply as this set of jurus use a very public shape, universal to all martial arts. For reasons described below, the metaphor name for this set could be called Jurus Gebyok. With these jurus we have the blueprint for how to arrange our motion and how to build our walls.

The orientation of a building is important in many cultures. The Chinese practice of Feng Shui dictates precise parameters for auspicious building. In Central Java, houses customarily face south as a way of respecting the South Sea. To outsiders these practices may come across as esoteric and superstitious. However these are usually founded on something more pragmatic. Facing south allows the breeze to pass through providing ventilation and comfort from the sweltering heat. [7] In IOPS Jurus Gebyok is the first jurus that forces the practitioner to keep track of their location and direction.

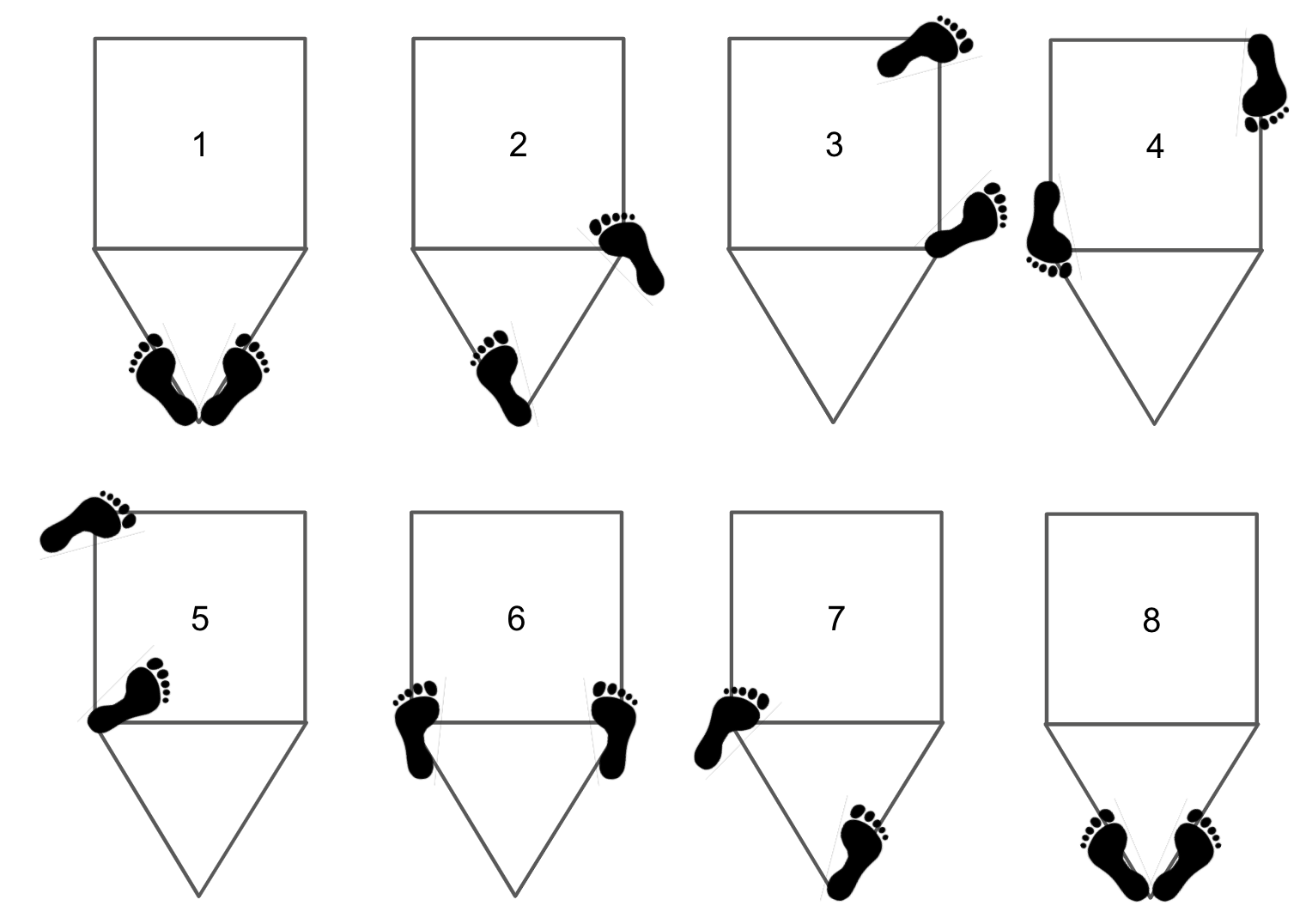

Construction of Joglo and other architectures is based on a complex numerology known as petungan which governs not only the dimensions of the buildings, but also dates of rituals and construction. “Traditional units of measure are based on anthropometric units known as named pecak (from the toe tip to the heel), asta (from the middle finger’s tip to the elbow), and depa (from one middle finger’s tip to the other when arms are stretched). These units differ from one building to another, being based on the owner’s or builder’s body.” [2] Thus even before construction begins, petungan measurement ensures the house is personalized to its owner.

This kind of measurement should be familiar to students of Inti Ombak as these pecak, asta, and depa measurements are used to modulate height of stances, to check alignment, and to measure reach and range. Petungan measurement is the key to differentiating Jurus Dasar Umum 1, 2 and 3.

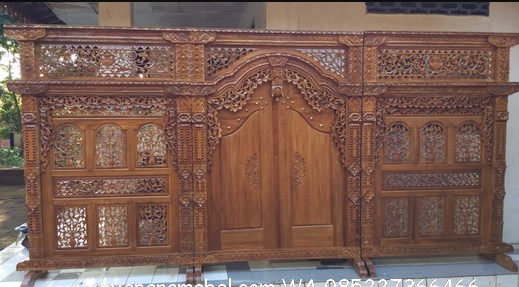

Gebyok is a traditional Javanese wall featuring a door and windows made from teakwood. They are often installed to partition the living room from the guest room, but may also be used as the main entry gate. The level of detail in gebyok signals a family’s status. These can range from simple and functional with a single door to massive with multiple panels and highly detailed with intricate carving.

In Javanese weddings gebyok serve as a decorative backdrop for the bride and groom. This symbolizes that a wall has been raised for a new home, but the rest still needs to be finished. In IOPS there are no weddings, but advancing past white belt is seen as a significant milestone. At this stage the student has passed from calon keluarga (prospective member of the family) and has accepted the new family.

Jurus Punden Berundak

Commonly taught as linear jurus or jurus lurus 1-4, these motions are a base that can be expanded into near infinite variety. Layered within these jurus are many of the motions that for the basis for proper and safe wielding of weapons such as clurit (sickle), cambuk (whip), cabang (truncheon/sai) and golok (Indonesian machete).

In keeping with the architecture analogy, the proper IOPS name for these jurus would be Jurus Punden Berundak. Punden Berundak or Punden Terrace are pyramid-like terraces. These are found in many building sites across the Indonesia archipelago including temples, such as the world famous Borobudur. [4]

While many houses from other Indonesian geographies are supported by stilts, Joglo architecture and others in Java are unique in their usage of the punden berundak. Whether stilts or terrace, a strong foundation relies on straight lines to ensure the house is level.

Jurus Saka Guru

The brief history of IOPS has two distinct eras in instruction. Some people learned jurus pisau #1 (knife jurus #1) first while others started with the empty hand version. Many from the latter group often think only the empty hand version is jurus saka guru while others from the older period may not know the term saka guru. To clear up any misconceptions, there is only one jurus saka guru. Whether it is using empty hand, knife, knife grips, staff, etc. the jurus is one; the expression and tools are many.

The compound word sakaguru has come to mean fundamental principle in Indonesian, but this meaning is not far removed from its architectural origins. The Wikipedia entry for Saka Guru get to the heart of the IOPS house metaphor.

Saka guru, or soko guru in Javanese, is the four main posts which supported certain Javanese buildings, e.g. the pendopo, the house proper and the mosque. The saka guru is the most fundamental element in Javanese architecture because it supports the entire roof of the building. Because of its importance, the saka guru is imbued with symbolism and treated with certain rituals.

Introductory paragraph from Wikipedia article on Saka Guru [5]

Saka guru consists of the word saka and guru. According to the Javanese text of Kawruh Kalang, the guru or “teacher” is a title given to the four wooden beams, while saka or “post” is for the four main posts. Thus the whole configuration is known as sakaguru, or more correctly sakaning guru or saka ingkang nyanggi guru (Javanese “the saka which supports the guru).

Symbolism paragraph from Wikipedia article on Saka Guru [5]

In Western architecture pillars and columns signal strength, stability and beauty. Banks and government buildings use pillars to tap into this psychology. Iconic buildings like the Greek Parthenon and the Lincoln memorial were designed to evoke awe. Like Roman pillars, sakaguru not only support the building, but are the visual centerpiece of the architecture.

Sitting atop the sakaguru posts is a pile of beams called tumpang sari. These beams tie the posts together and support the rafters. Tumpang means overlapping and sari means essence. “the outermost band of beams support the rafters of both the upper and lower roofs, while the heavily-ornate inner band of beams create a vaulted ceiling in the form of an inverted stepped pyramid.” [9]. Like with Gebyok, the level of detail and the height were used to show status and wealth.

In performing jurus saka guru, the IOPS practitioner should know the motions’ function, but should also develop the ability to layer flower over the core structure.

Kayu Usuk

The kayu usuk or rafters, provide the support structure to lay a roof. Extending out from the tumpang sari to the edge of the house these beams draw the compressional force exerted on the saka guru into tensional force which is routed out to the external posts/pillars. The spacing of these rafters dictates the size of tile shingles.

The IOPS corollary isn’t a jurus, but rather are the set of drills know as sinambungan. The word sinambungan (pronounced seen-ahm-boong-on) means flow and is roughly equivalent to sinawali drills seen in Filipino martial arts. Sinambungan consists of 5 templates which expand to 25 foundational movements. These drills teach awareness of angles, how to intercept and redirect attacks, timing, chambering, power generation and more. Used correctly they can be woven into any other jurus.

Jurus Balairung

Balairung is a term from the Minangkabau people of Western Sumatra used to refer to a large meeting hall used to reach consensus. Like the rumah gadang of the region, traditional balairung feature pointed roofs resembling the horns of a water buffalo.

The term balairung itself has been adopted into general usage in the Indonesian language to mean a townhall where people gather. In this sense the architecture is not strictly Minangkabau. For example the balairung at the University of Indonesia resembles the large pendhapa of the Keraton known as bangsal kencana.

Within IOPS, jurus pisau #2 (aka knife jurus #2) is formally named jurus balairung. With its four unique fisherman knife grips, opportunistic targeting and house-shaped footwork, the concepts from this jurus enables the practitioner to bring together all the foundational knowledge in one place. From foundation to roof, the house is structurally complete.

Limits of the metaphor

While the structure of the House of IOPS follows a construction or engineering progression, teachers may not choose to introduce the material in this exact order. Building a curriculum is often about scaffolding not only to sequence knowledge and skill, but also to tap into motivation. For massive, structured classes the ordering from the house metaphor can provide consistency in training and delivery of the material. If the goal is personalization of the learning experience, a different progression may be more warranted.

When looking at a building the layperson will neither look for nor appreciate the foundation and walls. Instead they will be drawn to major features such as the pillars, the roof and carvings. An attentive teacher will allow the beauty of form engage the student instead of imposing a functional order from day one. Conversely, someone from a scientific background may find the House of IOPS ordering more intuitive for learning. Or different again, an experienced martial artist may first come to IOPS looking to collect advanced or exotic techniques, and only after spending lots of time learning the flash of jurus balairung or beyond do they feel motivated to ask for the foundations like jurus tangguh geluk. A teacher putting IOPS kaedah to practice will find a way to give the student what they need without feeling limited by the tools.

One could argue that the house metaphor applies to other styles and arts. When applying this lens be careful not to assume the House of IOPS metaphor applies directly to other Pencak Silat schools. While Joglo is central to IOPS, for other schools a different building style may be more apt — if the house metaphor applies at all.

Closing Thoughts

The joglo is an accomplishment of vernacular architecture. It can be both constructed and torn down in a relatively short amount of time. Developed before many of the materials and techniques of modern engineering were available, the joglo exhibits superior climate management and resilience to new construction. Ironically when a massive earthquake hit Yogyakarta in 2006, the solid cement buildings quickly turned to rubble. Traditional rumah adat were resistant to the gempa bumi‘s strong shearing force, and if there was damage they were more easily repaired than their modern counterparts.

What looks like a straightforward design hides many complex hidden details. Readily expandable, joglo allow for a wide variety of configurations and floor plans. While all Joglo share common elements, Joglo construction is not one size fit all. Each house is matched to the personality and needs of its owners. Remember these traits as you build your own House of IOPS.

Bibliography

- Subiyantoro, S. (2011). THE INTERPRETATION OF JOGLO BUILDING HOUSE ART IN THE JAVANESE CULTURAL TRADITION

- Satwiko, Prasasto (1999). Traditional Javanese Residential Architecture Designs and Thermal Comfort. A Study Using a Computational Fluid Dynamics Program to Explore, Analyse, and Learn from the Traditional Designs for Thermal Comfort

- Spillway, In Wikipedia

- Punden Berundak, In Wikipedia

- Saka Guru, In Wikipedia

- Kalvpavriksha, Joglo and Limasan: the Art of Javanese Housing, Medium article

- Idham, Noor Cholis Javanese vernacular architecture and environmental synchronization based on the regional diversity of Joglo and Limasan

- Wisno Furniture Finishing – Gebok

- Joglo, In Wikipedia

- Balairung, In Wikipedia

- Rumah Gandang, In Wikipedia